Friday 29 April 2011

Photography and painting: a symbiotic relationship.

Imagine being a portrait painter in the 1840s and watching with some concern, the growth in the popularity of this bastard child of art and science called 'photography'.

Photography, created in 1839, was tied closely to the conventions of art at the time and early photographs mimicked, not only the subject matter of paintings, e.g. still lifes, portraits and landscapes, but some even tried to look like a painting by manipulating the plate to give the impression of brush strokes. So photographers initially tried to give this new medium some status by trying to produce photographic paintings. But with the sensitivity of early plates, especially to blue, skies were often washed out. Landscape painters could show up this limitation by 'completing the picture' you, might say. For example: Gustave Courbet's 1874 painting of Chateau de Chillon

can fill in the washed out sky and mountains of Adolphe Braun's photograph of c.1863-65:

Portrait painters painted the emotion of the sitter but photography showed the real emotion, the real person and this shocked but fascinated people. Take Julia Margaret Cameron's portrait of J.F.W. Herschel of 1867 and I think you'll see what I mean:

The power of these photographs must have alarmed portrait painters. Edward Steichen's striking portrait of JP Morgan made artists go in the opposite direction, e.g. Matisse's 'green stripe lady'.

On top of this, the detail in photographs could be looked at very closely whereas, the closer you got to a painting, the more you saw the paint strokes. Painters painted the light coming from the object and close up, it just looked fuzzy.

Early photographs were in monochrome so shapes were easier to define and use, creating more artistic images such as Timothy O'sullivan's survey work:

Photographers also had to frame their image but of course artists didn't have to, allowing some 'artistic license in the accuracy of their work. In fact, when photography took over the role of 'recording the world' from painters, it allowed painters to stop representing the world and experiment. Photography could also explore the emotions that painters used and produce what is often termed 'pictorialism'. Alvin Langdon Coburn's photograph of a bridge in Venice, for example:

Some painters, quite early on, used photography to record the human body in various poses to help in the construction of paintings. Thomas Eakins is a good example of this:

At the early stages of photography, there were two things photographers couldn't do - complete abstract images and very large images. This was an area where painters could deflect attention away from photography back onto themselves. Picasso was, not only painting figures and portraits in a way that no photograph could do, but was depicting the horrors of war, as well as, if not better than any photographer.

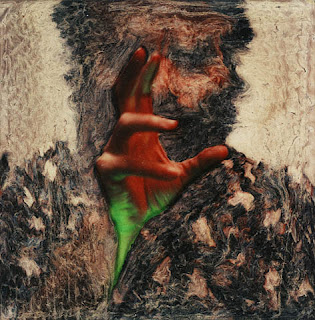

Jackson Pollock removed any subject matter from the paiting and his image was all about the material, i.e the canvas and the paint (not to mention the evidence of his presence on the canvas). How do you compete with that photographers? Well, Lucas Samaras put his 'mark' on his polaroids as they were developing.

Did Duchamp get inspiration from Muybridge for his 'Nude descending a staircase'?

Dorothea Lang and Robert Frank may well have been inspired by social realist painters. Maybe not James Guthrie of the Glasgow Boys, but I think you can see what I'm suggesting.

Some photographers use photoshop, make up and props to get their photographs to look like old paintings, e.g. Cindy Sherman

And, most recently, painters have gone to amazing technical lengths to make their paintings look like a photograph (often a bad photograph to begin with too!). Alyssa Monks is a fine example of this craze.

Thanks again goes to Jeff Curto's History of Photography. This blog was based on his Spring 2011, class 6.

Saturday 23 April 2011

The key to failure?

I subscribe to a UK magazine called 'The Word' and this morning I was enjoying Robbie Robertson (he of The Band) having a snigger at all the young bands (Fleet Foxes, Midlake, Iron and Wine, etc,) trying hard to look like The Band did on the cover of the Album 'The Band'.

The photographer, Elliot Landy wanted to shoot them at a spot in Woodstock. It was raining that day and the members of The Band just look pissed off at being there. They were wet and bedraggled, mostly bearded, unshaven and looked like backwoodsmen after a good night out. This 'look' has become the thing to aim for by some young new bands, much to the amusement of Robbie Robertson. He states, "I'm somebody who was always looking for what was not going to be trendy..." He goes on, "We just wanted to be learning our craft and absorbing enough music so we could make something with it's own character."

I thought that last statement should be the 'mantra' for all creative people.

I also read Scott Bourne's blog which echoed these sentiments. He wants us creative people to plough our own furrow and ends with the great Bill Cosby quote which I have used in the title of this blog:

And remember what Bill Cosby said…

“I don’t know the key to success, but the key to failure is trying to please everybody.”

The photographer, Elliot Landy wanted to shoot them at a spot in Woodstock. It was raining that day and the members of The Band just look pissed off at being there. They were wet and bedraggled, mostly bearded, unshaven and looked like backwoodsmen after a good night out. This 'look' has become the thing to aim for by some young new bands, much to the amusement of Robbie Robertson. He states, "I'm somebody who was always looking for what was not going to be trendy..." He goes on, "We just wanted to be learning our craft and absorbing enough music so we could make something with it's own character."

I thought that last statement should be the 'mantra' for all creative people.

I also read Scott Bourne's blog which echoed these sentiments. He wants us creative people to plough our own furrow and ends with the great Bill Cosby quote which I have used in the title of this blog:

And remember what Bill Cosby said…

“I don’t know the key to success, but the key to failure is trying to please everybody.”

Wednesday 20 April 2011

Is photography still our window to the world?

I was listening to Jeff Curto's Spring '11 Class 5 on Photography as transport in the 19th Century and it made me think about how difficult it is for photographers nowadays to bring a new image of the world which we hadn't seen before, into our lives. Haven't we seen it all by now? Some of the amazing BBC/Discovery/National Geographic documentaries I've watched took to me places I never imagined existed. Some I have an urge to travel to and the means of transport is available to me (but, alas, maybe not the finance!). Some places I think we've seen too many times and they have lost their allure perhaps.

In the 19th century, technological and chemical advances made it possible to take camera equipment out to the great wildernesses, and demand for images of the unseen world made it viable to capture the 'new world' and all its wonders. Coinciding with this was the transport revolution which made it possible for people to travel further afield and perhaps start a new life. In such cases, it would be beneficial to 'see' the terrain, the landscape and just exactly what the 'wild west' looked like. (Jeff's talk concentrated mostly on American examples.)

Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote about travelling all around the world sitting by you fireside and how marvelous it looked.

Carleton Watkins' images of Yosemite made it a place of wonder and beauty.

In the 19th century, technological and chemical advances made it possible to take camera equipment out to the great wildernesses, and demand for images of the unseen world made it viable to capture the 'new world' and all its wonders. Coinciding with this was the transport revolution which made it possible for people to travel further afield and perhaps start a new life. In such cases, it would be beneficial to 'see' the terrain, the landscape and just exactly what the 'wild west' looked like. (Jeff's talk concentrated mostly on American examples.)

Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote about travelling all around the world sitting by you fireside and how marvelous it looked.

Carleton Watkins' images of Yosemite made it a place of wonder and beauty.

Eadweard Muybridge (yes, the guy who did the multiple images of movement) did some technically brilliant landscape shots too.

The American Civil War photographer Timothy O'Sullivan also did work for surveyors so his photographs were perhaps the least picturesque but he still recorded, with some style, the land as it was about to be 'opened up' via railways, etc.

Andrew J Russell helped document the trans continental railway construction in America which helped investment and exploration. His images often had people in them.

William H Jackson realised that for Americans, devoid of all the grand churches and man made monuments so prevalent in Europe, the landscape had become their 'cathedrals'.

So what part of the world can photographers bring into our lives today that we haven't already seen? Well, maybe that's the wrong question. A better question might be 'what can a photographer bring into our world that we should see? The consequence of travel, industrialisation, urbanisation and the rapid population growth perhaps.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)